False consciousness permeates our being in such convincing ways that everyday truths are obscured and distorted by dominant ideologies.

Margaret Ledwith

This is Part 2 of a series of posts designed to help us explore our work and leadership through the lenses of dominant power and liberatory power.

What is dominant power?

Dominant power is when power is used to (consciously or unconsciously) disadvantage, impose, influence, coerce, control, exploit or manipulate in a way that undermines the humanity, wellbeing and freedom of another group or individual. The effect of using power in this way is dehumanisation, marginalisation and exploitation. Inequities exist when spaces (institutions, systems, classrooms) are designed intentionally or unintentionally to reflect, reinforce, reproduce and normalise dynamics of dominant power.

Because of the pervasiveness of these dynamics it is rare to find any space in a society that is not in some way affected by them. This is true not only of the systems we seek to transform but also the organisations we build, the relationships we engage in and the ideologies that shape how we understand ourselves and others.

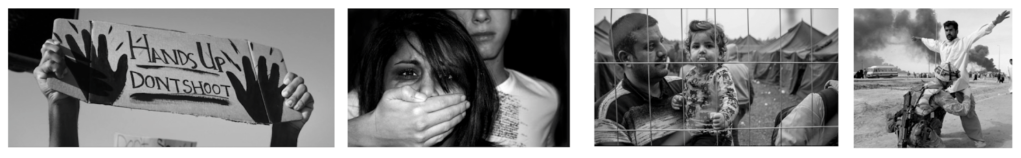

Dominant power expresses in many ways. It’s the bullying in playgrounds, it’s having to hide who you love, it’s skin whitening products, it’s not knowing if you will be able to afford your next meal, it’s the forced marriage, it’s having to pretend to be somebody else, it’s changing your accent to sound more ‘intelligent’, hiding your culture to be accepted, it’s hoarding wealth while people starve, it’s police brutality, it’s non-profit organisations that don’t reflect the communities they serve, it’s imposed markers of success, false histories, the theft of indigenous land, it’s economic exploitation, it’s being sold into slavery, it’s shame about your body, it’s refugee’s drowning in oceans, children scarred by war, it’s sexual harassment from your boss, it’s not seeing yourself in your school curriculum, it’s domestic violence, it’s being punished for asking questions, it’s media monopolies controlled by the powerful, it’s believing some lives are worth more than others, it is believing ‘the other’ is inferior and should be feared, it’s believing you are not enough.. (the list goes on)

Dominant power is also the energy that drives our relationship to the earth. The way we treat our planet – as a resource to exploit and dominate over, rather than as the source of life to which we are intimately entangled and dependent upon. The way we relate to ourselves, each other, and the earth is all interconnected. Unless we transform these relationships we risk extinction.

When we look at our education systems through the lens of dominant power we begin to recognise dominance is the energy that shaped it, the energy that sustains it, the energy it produces, and the energy that it serves. This is true beyond education too, it’s institutionalised in all our systems, entrenched in our cultures, and internalised so deeply within us that we may not notice it until we are offered critical points of reference and moments that challenge deep reflection. And so if we are to create transformational change that leads to equity and justice we need to learn how to wake ourselves up and tap into a different kind of energy. This energy is our libratory power. (We will explore this in more depth later)

How has dominant power shaped our world?

Dominant power has been present in our world for as far back as we have recorded history, especially after the agricultural revolution which allowed people to begin hoarding resources and use them as a way to control others, and then soon after with the emergence of kingdoms and then empires. However, there are also many examples of people who had (and many that still have) different ways of organising power that challenge many of our assumptions about how things have always been. There are also many Indigenous traditions that have and continue to challenge the status quo despite centuries of repression. It is important to acknowledge this because it reminds us that dominance is not inevitable, other ways of being together are possible.

The origins of our desire to dominate over others is a deep philosophical and spiritual question that we may never be able to fully answer. However, what we do know is that this desire has been mechanised and weaponised in many ways throughout history. One of the most pervasive examples of this is Western European colonisation and the ideological, cultural and economic models it imposed globally.

‘Formally’ many of these empires no longer exist but the colonial model they imposed is still very much with us and continues to evolve. We have inherited a world shaped by this historical legacy, and within societies designed to feed, protect and reproduce these dynamics. Sometimes this is obvious and easy to see, but often it is hidden and disguised. This means that we need to look critically at the past to identify the forces that have shaped our present reality and the systems we live and work within.

To understand how history shapes the present, we need to consider both our shared global history and the histories that are specific to our local contexts. Although there are consistent patterns that play out broadly, every context is unique and has evolved in different ways. Exploring our historical journeys both globally and locally, and the relationship between the two, can help us understand the underlying ideologies and events that have shaped our present realities and the nuanced ways in which they express today.

Watch:

*The videos featured in this post were produced for Teach For All.

Reflect:

Take a moment to consider these questions..

- In your local/national context, where has dominant power expressed throughout history? (When has the full humanity, freedom, rights, culture of people been oppressed.. Along what different lines of identity did this happen?)

- How has your local history been influenced by global hitory? (Consider the ideological, cultural and economic influence of: colonialism, industrialisation, capitalism, fascism, communism etc.)

- Where do you see this reflected in your education system and the broader system?

- Do you have the information you need to answer this question? Who has had the power to write the ‘official’ account of history? Who’s narratives have been left out or suppressed? How can you learn from the narratives of historically oppressed groups in your context?